According to Ludwig Wittgenstein, contemporary philosophy can only really be concerned with language. If this is true of philosophy then, without wishing to seem to state a necessary truth, it could equally well apply to contemporary art.

As in every apparently closed system, even that of art will have as its origin, object and probable goal the linguistic experimentation of its means.

In his celebrated book Le degré zéro de l’écriture, published at the end of the 1950s, Roland Barthes called for a sort of new Revelation of Literature (a wish paradoxically sceptical given its enclosure in a Utopian space) which was preparing its advent through a form of writing that had shifted play to a neutral ground. Writing – and obviously art too – was, or at least appeared to be, in a sort of cul-de-sac. On one side, it had at its disposal a body of rules and conventions (The Legend of Literature) which distanced the writer from the present. On the other side, should the writer desire to open his writing up to the “current freshness” of the world, he could only make use of a “dead and splendid language”. The tragedy and instrumental inadequacy of the artist before the world was tackled from the 1960s on using “neutral” linguistic methodologies which we all know as conceptual, minimal and pop art. After the 1980s, during which time neutrality was again mixed with the languages of the “past” giving rise to anachronistic and inconclusive elaborations, more significant experiments emerged which tried to revitalise back to neutrality the dead and splendid language of art. In the Utopian sense, Barthes held that the problem of writing, after its sojourn in the neutral field, would be resolved through a superior moral work leading to a “universalness” in which writing and society would be capable of living together in a uniform way.

More realistically, and with the advantage of time, the artist – unable linguistically to achieve the “freshness of the world” and the alienation of history – decided to reinforce the autonomy and separate identity of his own linguistic system, reformulating it in a transitive way.

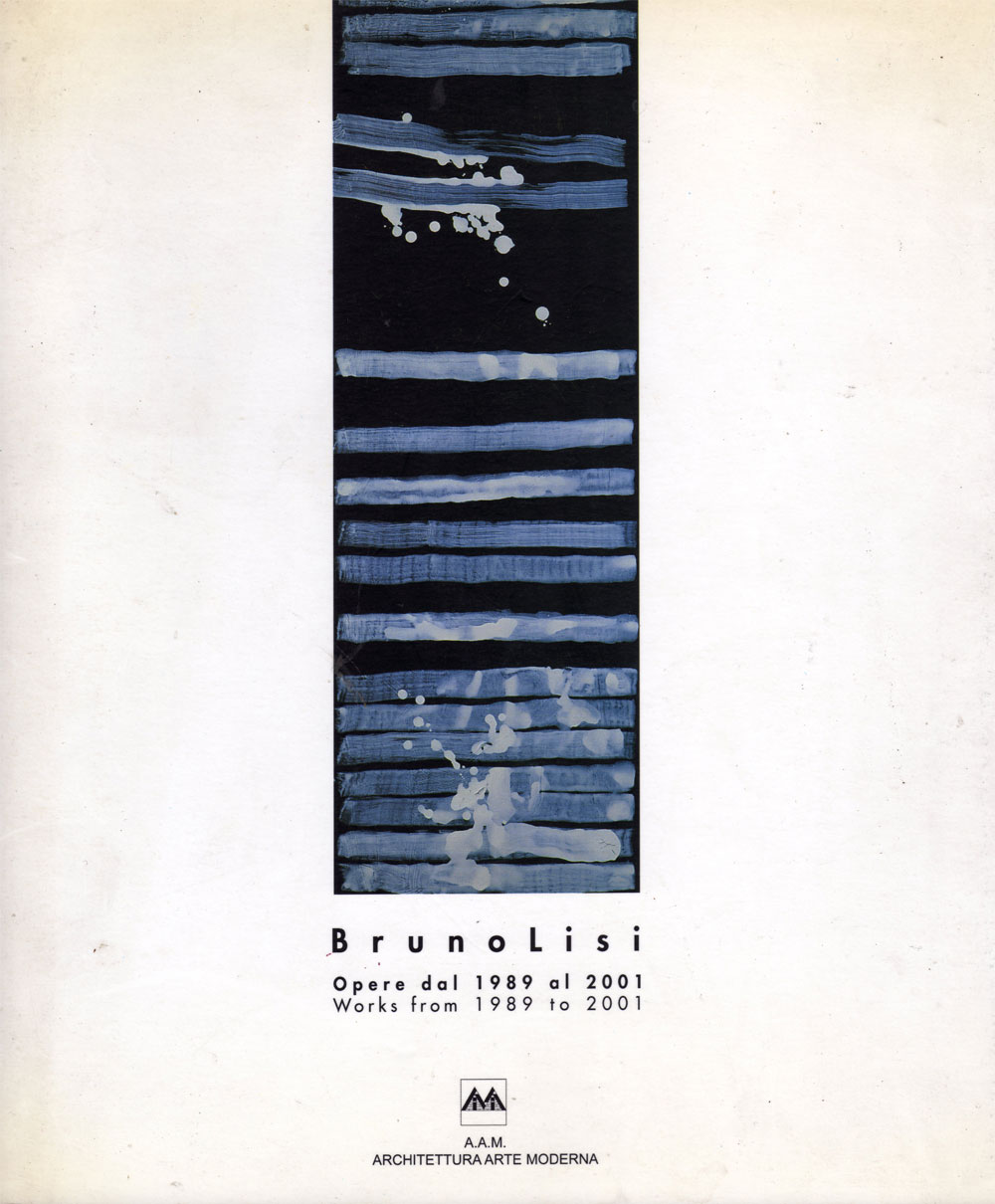

In the works of Bruno Lisi – and in particular the Segno series from 1993-2000 – the linguistic problem manifests itself essentially as the search for expression. Expression of the form which is constructed or veiled, however in this case both terms are actually pleonasms since there is neither direction nor track in his works, but rather the deliberate will to represent a movement. In such a way, signs and images detach themselves from a coercive system of pre-established meaning, proposing themselves not as idealistic models but as mere appearance inside a linguistic circuit from which, with some worry, one tries to snatch out a word to come. Without getting lost in exuberance and hyperbole, Lisi uses his modern conjuring lamp, probably showing that elsewhere – made of memories, “linguistic tricks” and mental associations – which is not legitimized by the rational order.

One of the essential elements of his work appears to be construction, intended as a balance between sign and language. His works are not just clearly defined intuitions, inventions that are subtle and essential from a formal point of view. They are above all peculiar and intelligent statements, obstinate affirmations of the autonomy of art. Things, objects become separated from their usual relations and become signs, traces which the artist gathers and recomposes, creating another reality, closed to the ordinariness of meaning, the arrogance of sense.

Lisi’s artistic language – which is both solid and light at the same time – asserts the contemporary artist’s possibility of continuing to exercise, in his own metaphysical reserve, the “linguistic” rights of utopia.

(translated by Michele Von Büren)

(from the catalogue of the exhibition, “Opere dal 1989 al 2001”, Galleria A.A.A. Palazzo Brancaccio, 26 November 2001-26 February 2002)